Radnóti, Miklós, Nachthemel, waak. Een keuze uit zijn poëzie uit het Hongaars vertaald door Arjaan van Nimwegen en Orsolya Réthelyi, Amsterdam 2023, (Uitgeverij van Oorschot)o

ELEGIE

De herfst is ingetreden, ook daarginds

waar vrijheidsvlaggen vallen; brandend bloed

druipt op de bladeren, gloeiend als sintels;

daaronder huivert zaad, zonder de moed

weer te ontkiemen! Want als zaad ontkiemt,

dan zullen heldenlijken, houten galgen,

of oorlogstuig dat warme nest opeisen,

naakt wacht het zaad dan tot de vorst invalt.

Grassprieten en kastelen zijn verkoold,

de dood jaagt boven voort, een woeste wind,

en in de middag, tussen as en rook,

vliegt een ontwaakte vleermuis rond, verblind.

Licht op, brandende streken in de verte,

in kou en stalen duisternis; de stromen

die gisteren hun milde streling boden

sidderen .kleumend onder bleke bomen.

Behoed mijn eenzaamheid, vermoeide herfst,

tijd heeft weer schaamte in mijn hart geklonken,

ik kauw op fraaie herfsten van weleer,

en leef verbeten als een winterstronk.

De ziel kan altijd meer en meer verdragen,

ik wandel wijzer, zwijgend, tussen doden,

met nieuwgeboren gruwel en geloof,

en sterren die hun leidend licht mij boden.

1936

IS DIT HET DAN …

Is dit het, angst, zelden een vliegend woord,

wat een volwassen, vruchtbaar leven biedt?

Ik leef in deze tijd, schim in een schim.

Heb ik geschreeuwd? Wanneer? Ik weet het niet.

O, schim in schim, het zwijgen in de stilte.

Regel na regel krast de pen maar door.

Ik wacht op wilde verzen -muggengonzen

in trage wilgen is al wat ik hoor.

Zovele vrienden, en de meesten zijn

alleen passanten van die pijn, die nood;

ik lig alleen, tussen herinneringen,

een vroege leerling, rijpend voor de dood.

Fluwelen duisternis brengt me geen troost,

doornen van woede sussen niet mijn zinnen,

ik lig hier zonder slaap en zonder hoop,

en zie het daglicht langs de muren klimmen.

In hopeloze dagen werd ik oud,

de dichter, jong en vurig, maakte plaats

voor een vermoeide, stramme logge man

die hijgend langs de oude wegen gaat.

Hij hijgt – en het bekoorlijk glooien wordt

een piek van doodsgevaar en heldenmoed,

wild is het pad naar de omwaaide top

dat hem uit deze lage tijden voert.

De wind waait van die kant met nieuws van ver,

en sist nu langs het opgeschrikte dak,

de jonge vrouw – licht valt op haar gezicht,

ze jammert in haar droom en schrikt dan wakker.

Schrikt wakker, slaap nog in haar zachte ogen,

opnieuw verlicht door de ontwaakte rede;

herleeft haar droom, kijkt rond en maakt zich op

een meer dan wilde wereld te betreden.

Kijkt rond – en even ligt haar koele hand

beschermend over mijn gezicht gebogen,

ik val in slaap met mijn vermoeide hart

haar adem strijkt vertrouwd over mijn ogen.

13 december 1937

SCHUIMENDE HEMEL

De hemel schuimt, daar zwalkt de maan,

ik leef nog steeds, wat mij verbaast.

De dood vindt niets dan witheid als

hij gretig in dit tijdperk aast.

Soms kijkt het jaar om, slaakt een gil,

kijkt nog eens om en valt in zwijm.

Een herfst sluipt weg achter mijn rug,

een doffe winter ging voorbij!

Het bloedend bos, de tijd die keert,

en uur na uur maar bloeden blijft.

De wind die steeds getallen, groot

en donker, in de sneeuwlaag schrijft.

Ik heb dat alles overleefd;

ik word verstikt door deze lucht,

omgonsd door lauwe stilte, als

was ik een ongeboren vrucht.

Hier sta ik stil, onder een boom,

giftig schudt hij zijn blad, een tak

grijpt naar beneden. Naar mijn nek?

Ik ben niet laf, ik ben niet zwak,

alleen maar moe. Ik zwijg. De tak

woelt zwijgend door mijn haren, bang.

Ik zou moeten vergeten, maar

zal niets vergeten, levenslang.

Schuim overspoelt de maan, hij smeert

de luchten vol met groenig gif.

Ik rol maar weer een sigaret,

traag en behoedzaam. En ik leef.

8 juni1940

PLOTS

Plots, in de nacht, beweegt de muur, een stilte

galmt in het hart, pijn schiet eruit, het gilt,

de ribben schrijnen, het gewonde kloppen

valt nu ook stil.

Lijf zwijgt en rijst, de muur slechts krijst in nood.

Hart, hand en mond beseffen al: de dood,

dit is de dood.

Lampen die knipogen in het gevang –

bewakers en bewaakten weten dan:

één lijf vangt alle stroom, de lichten zwijgen,

door alle cellen glijdt een schaduwgeest,

cipiers, gestraften, kakkerlakken ruiken

het schroeiend vlees.

20 april 1942

WINTERZON

Sneeuw smelt, verbaggert,

kroelt rond je schoenen.

eetketels dampen,

gebakken pompoenen.

IJspegels rekken zich,

druppelen zwaar,

spatplasjes, braafjes

de hemel in starend.

Daar, van de hemelplank

glijdt de sneeuw neer,

ik zwijg nu, twisten

doe ik niet meer.

Wacht ik op eten?

Mijn laatste uur?

Zal ik als ziel dan

door dag en nacht schuren?

Druillicht. Mijn schaduw

die naar me staart.

Ik draag een veldpet,

de zon een flambard.

26 december 1942

FRAGMENT*

Ik leefde op de aarde in een tijd

waarin de mens, ontaard, niet enkel doodde

in opdracht, maar vrijwillig, uit genot;

een waangedachte dreef hem, en doorvlocht

zijn leven met uitzinnig zelfbedrog.

Ik leefde op de aarde in een tijd

waarin verklikken eervol was; verraders

en moordenaars en rovers waren helden, –

en zelfs wie zweeg, niet juichte met de rest,

werd diep gehaat, gemeden als de pest.

Ik leefde op de aarde in een tijd

waarin wie sprak zich beter kon verbergen

en zich in schaamte op zijn knokkels bijten,

het land grijnsde de gruwel tegemoet,

zwolg in zijn lot, dronken van vuil en bloed.

Ik leefde op de aarde in een tijd

waarin een moeder vloek was voor haar kind,

een miskraam zegen voor een vrouw; wie leefde

benijdde wie al voer voor wormen was;

het gif schuimde op tafel in zijn glas

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Ik leefde op de aarde in een tijd

waarin de dichter enkel nog kon zwijgen

en wachtte tot hij weer zou kunnen spreken –

van één was ooit de juiste vloek gehoord:

Jesaja, meester van het gruwelwoord .

. . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . .

19 mei 1944

Miklos Radnoti: Modern English Translations of Holocaust Poems with a Brief Biography

Peace, Dread

I went out, closed the street door, and the clock struck ten,

on shining wheels the baker rustled by and hummed,

a plane droned in the sky, the sun shone, it struck ten,

I thought of my dead aunt and in a flash it seemed

all the unliving I had loved were flying overhead,

with hosts of silent dead the sky was darkened then

and suddenly across the wall a shadow fell.

Silence. The morning world stood still. The clock struck ten,

over the street peace floated: cold dread was its spell.

1938

(translated by Zsuzsanna Ozsváth and Frederick Turner)

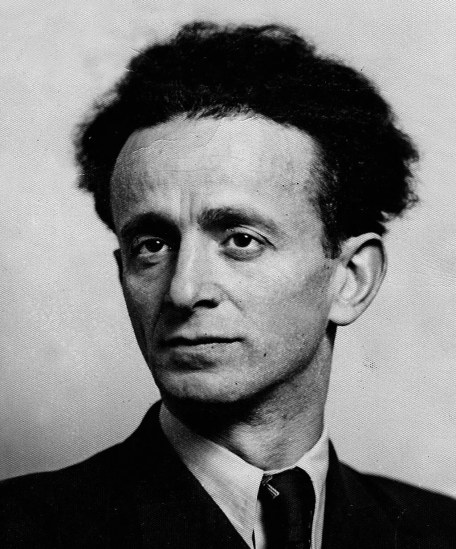

Miklós Radnóti [1909-1944], a Hungarian Jew and fierce anti-fascist, was perhaps the greatest of the Holocaust poets. Before Radnóti was murdered by the Nazis, he was known for his eclogues, romantic poems and translations. He was born in Budapest in 1909. In 1930, at the age of 21, he published his first collection of poems, Pogány köszönto (Pagan Salute). His next book, Újmódi pásztorok éneke (Modern Shepherd’s Song) was confiscated on grounds of “indecency,” earning him a light jail sentence. In 1931 he spent two months in Paris, where he visited the “Exposition coloniale” and began translating African poems and folk tales into Hungarian. In 1934 he obtained his Ph.D. in Hungarian literature. The following year he married Fanni (Fifi) Gyarmati and they settled in Budapest. His book Járkálj csa, halálraítélt! (Walk On, Condemned!) won the prestigious Baumgarten Prize in 1937. Also in 1937 he wrote his Cartes Postales (Postcards from France); these poetic “snapshots” were precursors to his darker images of war, Razglednicas (Picture Postcards). During World War II, Radnóti published translations of Virgil, Rimbaud, Mallarmé, Eluard, Apollinare and Blaise Cendras in Orpheus nyomában (In the Footsteps of Orpheus). Conscripted into the Hungarian army, he was forced to serve on forced labor battalions, at times arming and disarming explosives on the Ukrainian front. In 1944 he was deported to a compulsory labor camp near Bor, Yugoslavia. As the Nazis retreated from the approaching Russian army, the Bor concentration camp was evacuated and its internees were led on a forced march through Yugoslavia and Hungary. During what became his death march, Radnóti recorded images of what he saw and experienced. After writing his fourth and final postcard, Radnóti was badly beaten by a soldier annoyed by his scribblings. Soon thereafter, the weakened poet was shot to death, murdered on November 9, 1944, along with 21 other prisoners who were unable to walk. Their mass grave was exhumed after the war and Radnóti’s poems were found on his body by his wife, inscribed in pencil in a small Serbian exercise book. Radnóti’s posthumous collection, Tajtékos ég (Clouded Sky or Foaming Sky) contains odes to his wife, letters, poetic fragments and his final Postcards. Unlike his murderers, Miklós Radnóti never lost his humanity, and his empathy continues to live on through his work. Beside his postcards and other poems and translations previously mentioned, Radnóti’s “Letter to My Wife” is an especially touching poem that deserves to be read and remembered. So I have also included my translation of one of Radnóti’s most intimate poems.—Michael R. Burch

Postcard 1

by Miklós Radnóti

written August 30, 1944

translated by Michael R. Burch

Out of Bulgaria, the great wild roar of the artillery thunders,

resounds on the mountain ridges, rebounds, then ebbs into silence

while here men, beasts, wagons and imagination all steadily increase;

the road whinnies and bucks, neighing; the maned sky gallops;

and you are eternally with me, love, constant amid all the chaos,

glowing within my conscience — incandescent, intense.

Somewhere within me, dear, you abide forever —

still, motionless, mute, like an angel stunned to silence by death

or a beetle hiding in the heart of a rotting tree.

Postcard 2

by Miklós Radnóti

written October 6, 1944 near Crvenka, Serbia

translated by Michael R. Burch

A few miles away they’re incinerating

the haystacks and the houses,

while squatting here on the fringe of this pleasant meadow,

the shell-shocked peasants sit quietly smoking their pipes.

Now, here, stepping into this still pond, the little shepherd girl

sets the silver water a-ripple

while, leaning over to drink, her flocculent sheep

seem to swim like drifting clouds.

Postcard 3

by Miklós Radnóti

written October 24, 1944 near Mohács, Hungary

translated by Michael R. Burch

The oxen dribble bloody spittle;

the men pass blood in their piss.

Our stinking regiment halts, a horde of perspiring savages,

adding our aroma to death’s repulsive stench.

Postcard 4

by Miklós Radnóti

his final poem, written October 31, 1944 near Szentkirályszabadja, Hungary

translated by Michael R. Burch

I toppled beside him — his body already taut,

tight as a string just before it snaps,

shot in the back of the head.

“This is how you’ll end too; just lie quietly here,”

I whispered to myself, patience blossoming from dread.

“Der springt noch auf,” the voice above me jeered;

I could only dimly hear

through the congealing blood slowly sealing my ear.

Translator’s note: “Der springt noch auf” means something like “That one is still twitching.”

Letter to My Wife

by Miklós Radnóti

translated by Michael R. Burch

Written in Lager Heidenau, in the mountains above Zagubica, August-September, 1944

Deep down in the darkness hell awaits—silent, mute.

Silence screams in my ears, so I shout,

but no one hears or answers, wherever they are;

while sad Serbia, astounded by war,

and you are so far,

so incredibly distant.

Still my heart encounters yours in my dreams

and by day I hear yours sound in my heart again;

and so I am still, even as the great mountain

ferns slowly stir and murmur around me,

coldly surrounding me.

When will I see you? How can I know?

You who were calm and weighty as a Psalm,

beautiful as a shadow, more beautiful than light,

the One I could always find, whether deaf, mute, blind,

lie hidden now by this landscape; yet from within

you flash on my sight like flickering images on film.

You once seemed real but now have become a dream;

you have tumbled back into the well of teenage fantasy.

I jealously question whether you’ll ever adore me;

whether—speak!—

from youth’s highest peak

you will yet be my wife.

I become hopeful again,

as I awaken on this road where I formerly had fallen.

I know now that you are my wife, my friend, my peer—

but, alas, so far! Beyond these three wild frontiers,

fall returns. Will you then depart me?

Yet the memory of our kisses remains clear.

Now sunshine and miracles seem disconnected things.

Above me I see a bomber squadron’s wings.

Skies that once matched your eyes’ blue sheen

have clouded over, and in each infernal machine

the bombs writhe with their lust to dive.

Despite them, somehow I remain alive.

Forced March

He’s foolish who, once down, resumes his weary beat, A moving mass of cramps on restless human feet, Who rises from the ground as if on borrowed wings, Untempted by the mire to which he dare not cling, Who, when you ask him why, flings back at you a word Of how the thought of love makes dying less absurd. Poor deluded fool, the man’s a simpleton, About his home by now only the scorched winds run, His broken walls lie flat, his orchard yields no fruit, His familiar nights go clad in terror’s rumpled suit. Oh could I but believe that such dreams had a base Other than in my heart, some native resting place; If only once again I heard the quiet hum Of bees on the verandah, the jar of orchard plums Cooling with late summer, the gardens half asleep, Voluptuous fruit lolling on branches dipping deep, And she before the hedgerow stood with sunbleached hair, The lazy morning scrawling vague shadows on the air… Why not? The moon is full, her circle is complete. Don’t leave me, friend, shout out, and see! I’m on my feet!

(translated by George Szirtes)

from “Razglednicas”

III.

The oxen drool saliva mixed with blood.

Each one of us is urinating blood.

The squad stands about in knots, stinking, mad.

Death, hideous, is blowing overhead.

IV.

I fell beside him and his corpse turned over,

tight already as a snapping string.

Shot in the neck. “And that’s how you’ll end too,”

I whisper to myself; “lie still; no moving.

Now patience flowers in death.” Then I could hear

”Der springt noch auf,” above, and very near.

Blood mixed with mud was drying on my ear.

(translated by Zsuzsanna Ozsváth and Frederick Turner)

It seems the fourth and final Postcard poem above was the last poem written by Miklós Radnóti. Here are some additional biographic notes, provided by two of his translators, Peter Czipott and John Ridland: “In a small cross-ruled notebook, procured during his labor in Bor, Serbia, he continued to write poems. As the Allies approached the mine where he was interned, he and his brigade were led on a forced march toward northwest Hungary. Laborers who straggled—from illness, injury or exhaustion—were shot by the roadside and buried in mass graves. Number 4 of the “Razglednicak” poems was written on October 31, the day that Radnóti’s friend, the violinist Miklós Lovsi, suffered that fate. It is the last poem Radnóti wrote. On November 9, 1944, near the village of Abda, he too was shot on the roadside by guards who were anxious to reach their camp by nightfall. Buried in a mass grave, his body was exhumed over a year later, and the coroner’s report mentions finding the “Bor Notebook” in the back pocket of his trousers. Radnóti had made fair copies of all but five poems while in Bor, and those had been smuggled out by a survivor. When his widow Fanni received the notebook, most of the poems had been rendered illegible, saturated by the liquids of decaying flesh. However, the only poems not smuggled out—the four Razglednicas and one other—happened to be the only ones still decipherable in their entirety in the notebook. In late summer 1937, Radnóti had made his second visit to France, accompanied by Fanni. Although this was a year before Kristallnacht, Hitler’s move into Czechoslovakia, and the first discriminatory “Jewish Law” in Hungary, there was plenty of “terrible news” in the papers, as mentioned in “Place de Notre Dame”: the Spanish Civil War, the Japanese invasion of China, and of course the increasing threats from Hitler’s Germany. Nevertheless, most of these poems, at least on the surface, are innocent snapshots that justify their French title, referring to picture postcards such as tourists mail home. Radnóti was likely alluding ironically to this earlier set with his final four poems, which have the Serbian word for postcard—in a Hungarian plural form—as their title. Reading the two sets together darkens the tones of the five earlier poems, and makes the later four all the more poignant.”

As Camille Martin wrote, “These last poems, written under the pressure of the most degrading and desperate circumstances imaginable, unfurl visions of delicate pastoral beauty next to images of extreme degradation and wild, filthy despair. They give voice to the last vestiges of hope, as Radnóti fantasizes being home once more with his beloved Fanny, as well as to the grim premonition of his own fate. This impossibly stark contrast blossoms into paradox: Radnóti’s poetry embraces humanity and inhumanity with an urgent desire to bear witness to both. Yet even at the moment when he is most certain of his imminent death, he never abandons the condensed and intricate language of his poetry. And pushed to the limits of human endurance and sanity, he never loses his capacity for empathy.”

Related page: Best Poems about the Holocaust